Karel van der Toorn—

In the early days of the Trump II administration, it became a popular game in newspapers and on talk shows: ranking the members of the president’s inner circle. Who has the greatest influence? The game is likely to go on for quite some time. Powerful people can be whimsical. Someone with the president’s ear today may be pushed aside tomorrow.

There are no winners or losers in the ranking game. In the end, no one really knows who is whispering what. We can only guess. One of the defining characteristics of an inner circle—which is all about informal power and influence—is its aura of mystery. There is neither a public record nor democratic control. Even though some members of a president’s cabinet may be part of the inner circle, the two do not necessarily coincide. In fact, the inner circle resembles the court of an absolute monarch more than it does the cabinet of an elected president.

Historically, the inner circle is a phenomenon that primarily flourishes under autocratic regimes. Here are two examples, the one from the realm of history, the other from the realm of religion. The first is about the Persian emperor and his seven “counselors,” the second about the God of Israel and his seven “angels of the presence.” The two examples are related, because the image of God surrounded by seven archangels mirrors the Persian court. The political realities of the Persian Empire informed the religious imagination of the ancestors of the Jews.

From the late sixth to the fourth century BCE, the Persian Empire was the largest the people of the Middle East had ever known, stretching “from India to Ethiopia” (Esther 1:1). Its rulers wielded absolute power. Instead of running their empire with an elected government, kings like Cyrus, Darius, and Artaxerxes surrounded themselves with seven “counselors” (Ezra 7:14). The book of Esther explains that these men had direct access to the king (they “saw his face”) and sat first in the kingdom (Esther 1:14).

Greek sources tell a similar tale. Xenephon calls these men “seven of the noblest Persians,” and Herodotus says they were the only ones who could go to the king unannounced to offer advice or ask a favor. They were closely involved in political decisions made at the highest level. In the Persian Empire there were many other people who exercised authority, like satraps and governors, but none of them was as close to the center of power as were the members of the inner circle.

When Judah and Samaria became part of the Persian Empire (toward the end of the sixth century BCE), their inhabitants began to picture their god in new ways. Over the course of centuries, the Jewish god came to resemble a Persian monarch: God the king became God the emperor. Since the days of King David, the king metaphor had become very influential, and like most religious metaphors, it had been borrowed from the social realities of the time. The human king was at the top of the power pyramid. In his likeness, the national deity was raised to the position of king of the gods. God was “the great king over all the gods” (Psalms 95:3).

Under the impact of the experience with the Persian superpower, however, Jewish unease with “other gods” turned into a form of monotheism. The traditional image of the divine council (with God presiding over his peers) lost its appeal. The other gods were demoted to the rank of angels—messengers and executives in the service of the Almighty. There were thousands and thousands of them—their host was beyond counting, as the texts say, reflecting the human experience with the countless officials and intermediaries that stood between the Persian emperor and his subjects.

Echoing the political realities of the time, God the emperor had his own inner circle, consisting of the “angels of the presence” (Jubilees 1:27, 29; 2:1, 18; 15:27). There were seven such angels (Tobit 12:15), and it is no coincidence that their number matches that of the counselors of the Persian king. Realities from down below were projected upon the invisible world on high. The privileged position of the seven angels—direct access to God—made them perfect mediators. They were the ones who read out the prayers of the faithful in the presence of God. Before, the predominant belief was that God listened directly to the prayers addressed to him. Now the new reality required the intervention of angels. They made a record of the spoken prayer and transmitted the message to God’s inner circle, where it was read aloud in his presence (Tobit 12:12). Raphael and his colleagues were not gods but angels, yet their special position raised them above the ordinary angels. The angels of the presence were archangels, the inner circle of the heavenly court.

There is no democracy in heaven, as they say. God has not been elected to the throne. The seven members of his inner circle do not owe their position to popular vote either. Like any other religion, Israelite religion is indebted to its social and political environment for the metaphors it has chosen to describe the imagined reality of the gods—or, in the Jewish case, the one God. That environment was far removed from modern democracy. The organization of the Persian court, with an all-powerful emperor assisted by seven counselors, proved an important source of inspiration for the religious imagination.

Because Israelite religion left a lasting legacy in the form of the Hebrew Bible, the metaphors of the past continue to inform the present. Even though we have moved to the reign of democracy, the inheritors of the Israelite legacy—Jews and Christians foremost—rely on religious metaphors from an earlier, predemocratic era. Religion tends to be conservative in its metaphors. Outdated, perhaps. Yet now that the days of the Persian Empire are returning—under a different name and with different players, but with an ideology just as ruthless and autocratic—the notion of God as emperor in heaven surrounded by an inner circle comes dangerously close to what we see happening here below.

Karel van der Toorn is professor and chair of Religion and Society at the University of Amsterdam. He is the author of Scribal Culture and the Making of the Hebrew Bible and Becoming Diaspora Jews: Behind the Story of Elephantine, among other publications.

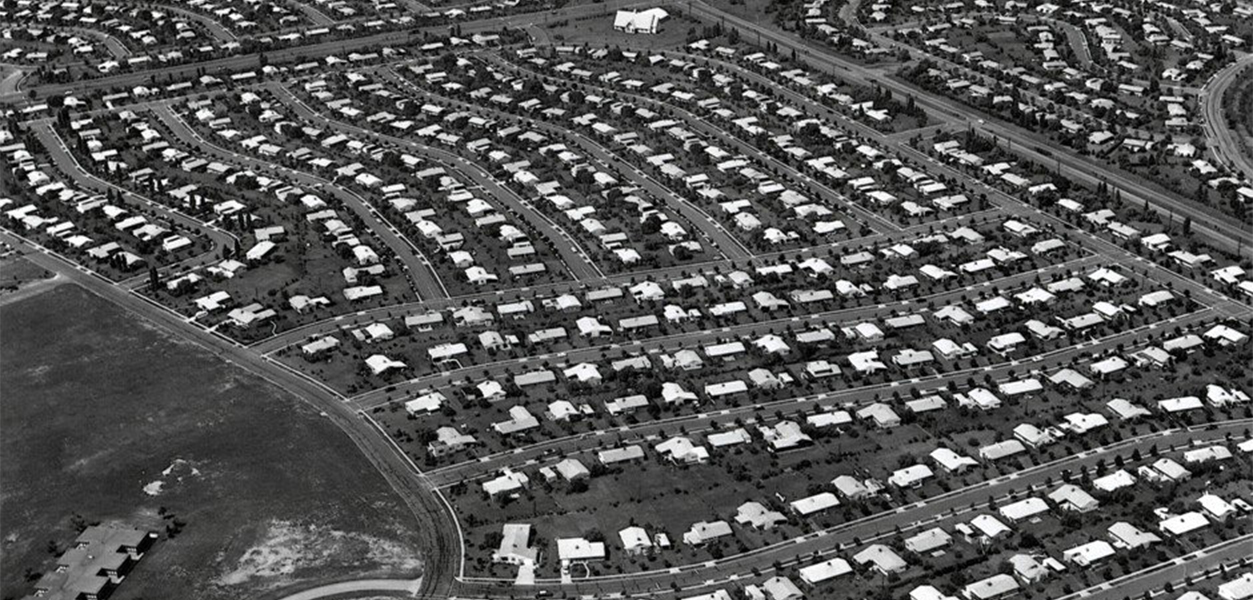

How Levittown Set the Stage for Today’s Housing Crisis

How Levittown Set the Stage for Today’s Housing Crisis